Writing these lists is so much more difficult than writing the best of the current year list - especially this year. These films are indisputably (okay someone else might dispute at least one of these) among the greatest ever made - smarter people than me have thought long and hard about these films and written incredible stuff about them. I’ve seen ‘em once (actually I’ve now seen Wings of Desire and The Sacrifice twice [edit note - and now also The Straight Story] - you decide if it helped) and they blew me away, and now I’m going to do my best to describe what I liked about them in a paragraph or two - god help me.

10 - Paris, Texas

Gorgeous from top to bottom - filled with a haunted and melancholy beauty. Everyone loves Harry Dean Stanton (Roger Ebert had the most iconic compliment for him - google it) and this is probably his best performance, staggeringly against type, but perfectly natural, effortless. Easy enough for a man who once said, “There’s nothing. There is no self”, but god are we lucky to see it. As we’ll see again later on this list, this was the year of Wenders for me - a director I whose work I had never encountered - in 2024 I fell in love with his newest film Perfect Days, declaring that it would’ve been my #1 movie of 2023 had I seen it in time (why not declare it my #1 movie of 2024? Maybe I should’ve, I dunno. I had a hard enough time deciding La Chimera and Evil Does Not exist counted as 2024 releases, give me a break).

Paris, Texas was my 3rd Wenders film of the year and I absolutely adored it. The scene in the booth at the end where Stanton reveals himself to his long separated young wife is incredible, and the way it works in concert with all the context we have in the film is remarkable. A story that can actually mesh with and explain a man walking alone in the desert for years - a worthy penance. There’s a little bit of play between the main characters of Paris, Texas and Perfect Days actually - one a man who isolates himself and speaks little because of harm he’s done, one a man who isolates himself and speaks little as a sort of therapy for an implied harm received. Wings of Desire (to be discussed later) fits in here as well - going off of these three movies you could project a cinema of loneliness onto Wenders. I’ll have to investigate further and see how true that is.

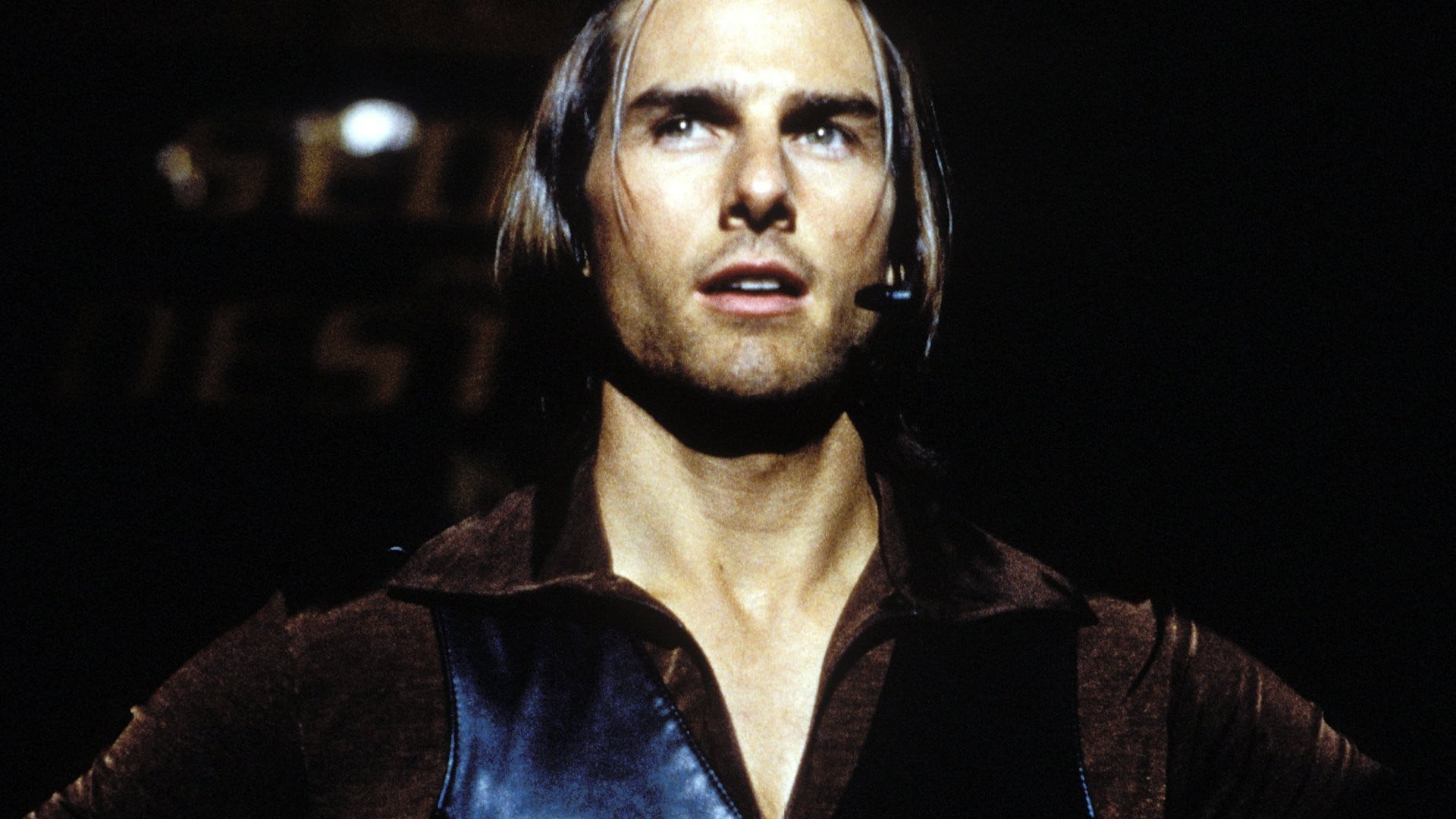

9 - Magnolia

Not my final PTA for completionist purposes but my final Major PTA. A filmmaker who has been acclaimed and beloved basically my entire life, and one I’ve had to grow into in a sense. I’ve never really been on PTA’s wavelength, always found his films a little cold and offputting (besides Boogie Nights - never had any trouble with that one), even as I couldn’t help but be impressed by their obvious overwhelming merits - the gorgeous shots, the incredible characters brought to life by some of the greatest performances of the modern era, the overpowering sense of a fully formed authorial vision (something only a very few modern directors exhibit). These qualities drew me in while some of the frictional qualities, the lack of resolution, the repellant characters, and just an inexplicable coldness that defies description even now, held me at arms length. As I’ve gotten older and seen more and more movies and thought more about movies and what I like and why, my tastes have matured.

I come to Paul Thomas Anderson’s work now as an old friend, a life-long companion who I’ve finally grown enough to understand at least a little. Like good wine or coffee or all the other subtle and bitter pleasures that can’t be appreciated by an undeveloped palette - the complexity and strange intertwined joys and disappointments of Anderson’s work that were so frustrating and cold to me as a younger viewer are now deep and nuanced and full of feeling that I am now ready to begin unpacking.

Anyway I guess I should bring this around to the movie in question - Magnolia is PTA at his biggest, longest, and densest (although maybe also his most scattershot). The joy of all these weird little people jammed into the otherworld of the city of angels - its spectacular. I come back to William H. Macy as the washed up former child quiz star all the time - what a magnificent performance, the kind of fallen angel that’s supposed to dot the LA cityscape in these kinds of stories. Reminiscent of Mickey Rooney, someone famous for being an archetypical child who’s never really able to grow up, ends up becoming a strange permanent adolescent, forever sad and lonely.

8 - Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

While I’m not a hardcore (get it) Paul Schrader guy, I’ve seen a handful of his movies and I always find them interesting, occasionally find them great. Mishima is of course “the big one” in his career (until First Reformed I guess, but Mishima still looms pretty large), and upon watching it you immediately see why. The enormous practical sets, the use of colour, the singular union of subject matter and artist. Schrader is doing things he never did before and never would again. (As far as I know anyway - like I said, my viewing percentage of his filmography is pretty low - maybe more work to be done). While I think the whole thing is great, it really is the incredible theatrical staging that elevates the film. Schrader’s tribute to Japanese culture and cinema (a lifelong obsession) the explosive use of bright colour in the theatrical sequences reminds me of early colour films by filmmakers like Kurosawa and Kobayashi, especially the way that they embrace the staginess of their sets for otherworldly sequences.

7 - Late Spring

In 2024 I whet my appetite for Ozu by watching Late Spring, one of his most beloved masterpieces and reading Schrader’s book Transcendental Cinema: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. (I also picked up a copy of Shiguéhiko Hasumi's Directed by Yasujiro Ozu, but I haven’t read that one yet). In 2025 I hope to really dive into Ozu’s filmography and immerse myself in his stories of generational conflict and societal pressures, and lock in on his rock solid framing and composition. That said - Late Spring: what a picture. It’s this quiet tragedy as two people pull themselves apart for no better reason than that that’s what society expects them to do - all this deeply felt emotion that can’t be spoken. So many scenes where two people sit in a room and specifically do not say the thing they are feeling, but we the audience can feel it anyway. With his locked down camera and incredible compositions Ozu is always able to draw depths of emotion and feeling out of actors' faces, even as they remain still, giving gentle smiles. The film is a masterpiece.

6 - 8½

One of the most magical films I’ve ever seen. From the first moments it is cinema as a wonderland, a dreamscape - dedicated to creating the kind of images that come to us all but rarely leave our heads. It’s kind of a movie about the inside of our heads as well - a movie about a director making a movie about himself - and so much of the movie is digressions into the director’s fantasies and dreams, extended jokes about the selfish and self-involved way he sees the world and others, a self-awareness that is of course, also self-serving - he’s putting it in his movie! But he can kind of get away with it because of course Fellini cast one of the most loveable rogues in film history as himself, Marcello Mastrioni, who is so charming he makes it all work, even when he’s winking at the camera. The final moments of this movie are incredibly beautiful and joyous, even if there’s also a kind of sad irony there - we can have this beautiful synthesis of everyone from your whole life joining hands and dancing together - because it’s just a movie. Movies can be the innermost images and desires made visible, but never made real - it’s all a trick. But it’s a nice trick all the same.

5 - Wings of Desire

Watched this one twice last year - on Criterion at home after seeing Perfect Days early in the year, then later at the Bytowne when the new remaster was shown. (Tragically I was unavailable when Paris, Texas came to town in the fall). In some ways I feel like this is THE Arthouse movie, it is kind of exactly what I imagined art films were like based on stereotypes in popular culture before I started watching them - and it rocks. Things like the use of voice-over as internal monologues, the constantly roving camera checking in on the lives of ordinary people with a focus on the tragedy of everyday life, the black and white dreariness, the central role a circus plays (art films are always stereotyped as being about clowns - possibly because the stereotypical art film is french? The circus in this one is french too, so there you go).

I think part of why Wings of Desire comes across this way may be that it was influential on the stereotypes and parodies of art films during the time I was growing up, but maybe also that in some ways it’s a synthesis of art film from the decades before its release. The internal monologue stuff presumably comes from Bergman (maybe also Tarkovsky?), I think there’s some french new wave influence as well (certainly the idea for the circus comes from french film), Peter Falk being a central character probably assisted by his roles in many Cassavetes films (or maybe Wenders just really liked Columbo - the random people in the film that see Falk on the street aren’t yelling out “I loved your work in A Woman Under the Influence”). Regardless of its influences, its triumphant - a movie that spends so much of its runtime pontificating about life and meaning and futility and death and the answers to those big scary questions being the simple joys of physicality - “when your hands are cold, you rub them together ...you see, that's good, that feels good!” Also Nick Cave is in this one - pretty neat.

4 - Pulse

Last year I put Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure on this list at #6 - Pulse is higher this year, but I’d say I like Cure better. Maybe last year was tougher competition - regardless, I really loved Pulse, as much as anyone can love a harrowing emptiness that burrows into your brain. Pulse feels like a movie far ahead of its time, in the way that it represents the creation of the internet as so damaging to the structure of reality that the souls of the dead begin leaking through it into the world of the living. That’s not exactly the information we get in the movie, but it’s somewhere in that ballpark.

There’s a lot of specificity to Japanese culture here, both in the metaphysical conception it’s working in as well as the cultural movement it was a part of - the new Japanese ghost stories that were part of the 90s/00s J-Horror movement often centered around two core ideas - 1) the evil spirits/ghosts that were part of traditional folklore and religious practice are still here, but modern society has lost the spiritual wisdom that was used to deal with these spirits in the past, and 2) modern society/technology has fundamentally changed the world in significant ways, allowing evil forces to interface with the world in new ways that society is not prepared for. Pulse is clearly playing in this same space, and on top of that working in the space of the economic downturn Japan was experiencing at the time - the themes of mass depression and suicide among young people, a feeling of directionlessness and pointlessness in life, these all track closely to the film’s specific moment. However it doesn’t take a genius to point out that these qualities are universal, and the film’s use of the internet as the central mechanism for the spreading of this haunting/depression makes it especially prescient. It certainly feels in 2025 like the internet was a vector for some haunted force that is devouring the world.

3 - Metropolis (2001)

Over 2022 and 2023 I read an absolute ton of manga. I discovered the incredible resource that is the local library and proceeded to read everything I could get my hands on, in particular everything available from the Godfather of manga/anime - Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka is the creator of Astro Boy, both in manga and anime form, and his work leading the production of the Astro Boy anime basically created the template for the Japanese animation industry. (A bit of a mixed bag given the brutal schedules it historically required, continuing to this day - this was one of the key innovations Tezuka’s studio pioneered). While Astro Boy might be Tezuka’s most successful creation (especially in the english speaking world), he was also extremely notable for moving beyond manga aimed at children and creating a number of more literary manga, works with deep and complex themes, many of them dealing with extremely dark or taboo subject matter. Metropolis (2001) isn’t really based on one of Tezuka’s more adult works, but it is incredibly representative of his concerns as an artist, and is a love letter to the man and his legacy.

Directed by Rintaro, Metropolis expertly deploys Tezuka’s signature style of character design, a relatively “cartoony” throwback to early Disney shorts and things like popeye and betty boop. Tezuka’s characters always looked like escapees from newspaper comic strips and after reading his work frequently for two years, it was such a delight to see those little faces on the big screen (Tezuka treated his favorite characters to draw as actors in a company - the same faces would pop up in all of his stories playing similar stock characters, like a character actor playing similar roles).

The movie is spectacular, drawing together Tezuka’s frequent concerns like authoritarianism, revolution, technology, and environmentalism - it has a killer jazzy soundtrack that feels right out of the era when the original comic was written, and it combines Tezuka’s old school character designs and aesthetic sensibilities with the cutting edge computer animation that was just starting to come into it’s own in 2001. Though Tezuka died in 1989, this final grand tribute to his work stands as a monument to the man and his legacy, raised by new stars in the industry he got off the ground.

2 - The Sacrifice

Just got to watch this for the second time, this time at the Bytowne - looks incredible on the big screen. Probably the most powerful final statement in cinema history - it’s a profound and awesome (in the classical sense) expression of finality. A biblical fable about a man given what he begged for by god and following through on the promises he made in his moment of desperation. It’s an incredible capper on Tarkovsky’s career, arguably the greatest filmmaker to ever live - from the first moments of the film he’s in The Zone, with a long and gorgeous tracking shot of a simple walk and talk - during this long tracking shot a man rides a bike, he gets pranked by a kid, people drive up in a car - all kinds of stuff happens, but the camera never cuts away. The second chunk of the movie is an extended gathering indoors, conversation stretches on as the day fades - the scene gets darker and darker as the natural light disappears, until darkness reigns and the television gives messages of doom - the scene where the news of disaster is introduced has some excellent blocking, a beautiful scene of people sitting around a table at low light to match Barry Lyndon.

The final sequence of the film is Tarkovsky’s fiery goodbye to cinema - an awesome spectacle with a tragicomic interlude - the camera slowly pulling back all the while. It’s one of Tarkovsky’s favorite tricks, making you just sit there and watch an unbroken take, focusing your attention, your patience - but this time you have total chaos to observe, with a Jacques Tati bit going on at the fringes. What a way to go.

1 - The Straight Story

I put off writing this long enough that now I have the deeply sad task of using the final entry on this list to eulogize one of the greatest filmmakers and artists to ever live, David Lynch. The Straight Story holds an interesting position in Lynch’s filmography, with the classic anecdote being that Lynch described it a the time as his “most experimental film” while to most viewers it might seem on the surface to be his most normal film. Certainly the straightforward narrative structure and lack of surrealist (or transcendentalist) symbolism makes it more immediately explicable to the first time viewer. It was immediately apparent to me upon viewing the film how it fit naturally into Lynch’s filmography, the presence of several of his key interests, and the sense of strangeness or otherworldliness in the everyday, so central to his oeuvre.

One constant theme in Lynch’s work is a fascination with people - all types of people, but especially ordinary people. I’m tempted to say that he loves them, but of course Lynch is constantly aware of and fascinated with the duality of people, so while I think there is love, it’s not the kind of “noble savage view of normies” meme version of a love of ordinary people, fetishizing the common man - Lynch’s work presents ordinary people (that’s us by the way, me and you as well) as the strange, beautiful, and sometimes frightening creatures that we are. The Straight Story is maybe the Lynch project that most centers on this theme - Twin Peaks is of course the other big one, but the people of Twin Peaks are so much more exaggerated, they’re takes on stock characters and sitcom tropes - the people of The Straight Story are really just people. Some of them are in tough situations, some of them are experiencing very strange occurrences, but none of them are outside of the realm of possible strangers you might meet in a random small town in North America. Growing up in a rural area outside of a small town, having met all sorts of grouchy old farmer types, volunteer firefighters, and local mechanics (and all the other flavours of local yokel that populate The Straight Story), the characters and performances in the film really rang true to me, and I felt a real delight in seeing these kinds of people on the screen, a delight that David Lynch clearly shares (“but that’s MY grabber Alvin!”).

The film really sings in the quiet moments of Alvin’s journey - when the camera soars up into the wild blue yonder of the open sky and Badalamenti’s excellent score absolutely goes bananas, it makes me cry at the beauty of the world. While Alvin’s journey across multiple states on a lawn mower is really about his deep need for reconciliation with his brother, the love he’s infused with and the regret he carries for letting their estrangement go on for so long (the difficulty of the journey being the message he’s sending more than anything he’ll say with words), I also think it’s a film about the inherent value of doing something the hard way for its own sake. David Lynch was a man who liked to do things himself. If you look at his youtube channel or one of the many other places he put out videos or talked about his life, you’ll see he was a man who loved to tinker, who loved projects, who loved to work with his hands. He didn’t have to do any of that stuff - work on furniture, do home DIY projects, repair his pants with glue and paint and paper towels. It makes me think of a couple things - the pleasure of physicality conveyed by Peter Falk (as himself) in Wings of Desire I already mentioned above - “when your hands are cold, you rub them together ...you see, that's good, that feels good!”, but also a sentiment expressed by Vonnegut towards the end of his life - “we’re here on Earth to fart around. And, of course, the computers will do us out of that. And what the computer people don’t realize, or they don’t care, is we’re dancing animals. You know, we love to move around. And it’s like we’re not supposed to dance at all anymore.”

David Lynch was obviously an artist of titanic proportions. His work was elemental, and stared directly at the dark heart of modern life, with specificity, honesty, and love. There are innumerable emotional truths and artistic lessons and imaginative ideas to be taken from his life and work, and we’ll be living in the aftermath of his career for the rest of our lives - if you’re my age, you already have been. But for a smaller, more applicable lesson to take from David Lynch’s life and career that every one of us can do today, is to do something. Be in the world by working with your hands or starting a project or doing something just the way you want to even if it isn’t the most efficient or straightforward way of achieving the goal. And when you do, imagine the man himself giving you a big thumbs up and saying “GREAT JOB, BUDDY!”